The Advent Season

Originally, the Advent season (in Latin, “adventus”, which means arrival) is meant to be a time of mental and spiritual preparation for the greatest Christian holiday of the year, the birth of Jesus on the night of December 24th.

The Advent spans the 4 Sundays before Christmas, beginning with the first Sunday after the 26th of November. The Advent season ends on December 24th after sunset, which marks the beginning of Christmas Eve. In the Roman Catholic Church, there were initially between 2 and 4 Sundays in Advent, until Pope Gregor the Great (pontificate 590-604) officially made it 4 Sundays.

Origin of the Advent calendar – the beginnings

The Advent calendar originated over the course of the 19th century in the German-speaking world. It had many predecessors, which arose more or less simultaneously in different places. While the Catholic Church celebrated the Advent with daily prayers in this time, in Protestant families this time of devotions and contemplation took place within the family. The Bible was read aloud, verses were recited, people prayed together and sung devotional songs.

Since time is an abstract value, and it is particularly difficult for children to grasp, around 1840 parents began to think up a variety of ways to illustrate the remaining time until Advent for their children in order to highlight the special, holiday atmosphere of the Advent season.

For example, families began to hang up pictures with Christmas themes on the wall or in the windows. Another variation was that parents made 24 lines with chalk – the Sundays were marked with longer or colored strokes – on cabinet doors or door frames. The children were then allowed to wipe away one stroke each day.

Little Christmas trees (in part, also handmade wooden frames) served as “Advent trees”. Every day little flags or stars adorned with Bible verses were hung in the trees. In some families, an additional candle was put on the tree and lit each day.The increasing light in the trees symbolized the approaching arrival of the Light of the World, Jesus Christ.

In some Catholic regions the children were allowed to place pieces of straw or feathers into the manger for their good deeds (!) each day, so that baby Jesus could lie comfortably. Even today this custom is still practiced in certain convent and monastery schools.

In Austria, creative parents made “heaven ladders”, a special type of Advent calendar. One progresses down the ladder rung by rung each day, illustrating the concept that on Christmas, God comes down to Earth.

In Scandinavia at this time, the custom emerged of dividing a candle into 24 segments and letting it burn down segment by segment over 24 days’ time.

In Buddenbrooks, Thomas Mann described a homemade tear-off calendar which the nanny Ida made for Hanno, her charge. “With the help of the tear-off calendar which Ida had made for him, and on whose last page a Christmas tree was drawn, little Johann followed the nearing of that incomparable time with a racing heart.”

At the end of the 19th century, creative parents made so-called “Christmas clocks”, with a round face divided into 12 or 24 segments, on which the hands could be moved one step further each day. Each segment was adorned with song texts or Bible verses.

Thus the Advent calendar became a way of measuring the days until Christmas Eve in order to demonstrate the remaining time to children and to heighten the anticipation of the Christmas celebration.

Printed Advent calendars – the Gerhard Lang era

The first printed “Christmas clocks” were produced in Hamburg in 1902 and were released by the publisher of the evangelical bookstore, Friedrich Tümpler. They cost 50 Pfennig.

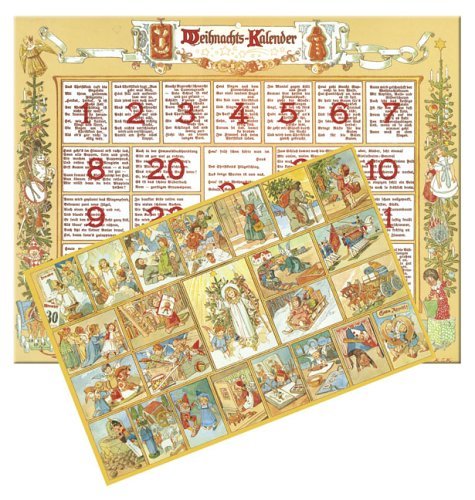

In 1904, the Christmas calendar “Im Lande des Christkinds” (In the land of the Christ child) appeared as an insert in the Stuttgarter Zeitung newspaper. It was based on Gerhard Lang’s (1881-1974) idea.

This calendar didn’t have any little doors to open, instead it was composed of two printed parts: one page contained 24 pictures to cut out, as well as a cardboard page on which there were 24 boxes, each with a poem composed by Lang.

The children could cut out one picture each day, read a verse and glue the picture on it. On December 24th the Christ child, dressed in white, was glued in place.

In his childhood, Gerhard Lang received a version from his mother which comprised a box of 24 “Wibeles”, a Swabian type of baked meringue, in order to make the time until Christmas Eve pass faster.

From 1908 onwards, Lang had his Advent calendar printed by the publisher Reichhold & Lang, and sold these in the following years in increasingly high numbers and in a variety of types – including a version with Braille.

Gerhard Lang worked passionately on the development of new variations, including the Christ child’s house, which one could fill with chocolate; Advent calendars one had to break open in order to get the contents; and ones with doors to be opened, as well as Advent trees with angels to hang up and the little Advent houses. The Advent house was comprised of four colored pieces of cardboard, which could be put together to make a house. The cardboard houses had windows and doors, which had colored transparent paper covering each opening. Starting on the 1st of December, one window would be opened each night, and on the 24th, the front door would be opened. When you put a candle inside, it cast a bright holiday glow.

Gerhard Lang was intimidated by neither cost nor effort when it came to developing new calendars; his prints stand out because of their high quality and attention to detail. Just a few years after Gerhard Lang began producing Advent calendars in larger print runs, other publishers started bringing out Advent calendars. By the 1930s, the Advent calendar was widespread in Germany.

In the end, Lange was no longer able to withstand the price pressure, and had to stop production of his calendars in 1940.

Advent calendars in the war era

With the outbreak of World War II, paper was rationed in Germany. At the beginning of the 1940s, the printing of illustrated calendars was stopped because it was considered “unimportant to the war effort”. In 1941, church-run media was forbidden. Instead, the National Socialist German Workers’ Party (Nazi party) produced its own national socialist calendar and distributed it among citizens. It was comprised of a small booklet which included stories, songs, sayings, as well as instructions for coloring and arts and crafts. The obvious goal was the reinterpretation of the Advent season: all church-related and religious elements were removed and replaced with symbols of the new ideology, with reference to supposedly Germanic roots. The Advent wreath became the Solstice wreath, the Christ child became the “child of light”. The German word “Vorweihnachten” (pre-Christmas) replaced the Latin term Advent, Saint Nikolaus was replaced by the Rider on the White Horse, which was then associated with the god Wotan.

Developments after World War II

Advent calendars were once again printed for Christmas in 1945; there was a strong desire to return to Christian values and the old traditions. Companies which hadn’t been destroyed and which had paper on hand once again published the motifs from before the war, among others.

After the first Advent calendars became established throughout the German speaking world in the 1930s, including in Austria and Switzerland, the Advent calendar was now positioned for worldwide success, and became widespread in Great Britain and the USA. Today, Advent calendars are printed by the millions in Germany, and more than half of them are exported for sale abroad.

Since their first beginnings in the 19th century, handmade Advent calendars have been individually designed and created with enthusiasm. It is no longer only children who receive Advent calendars as gifts; adults also give each other Advent calendars, and children make them for their parents.

While the shape, type and appearance of Advent calendars has changed over time, the mission of the Advent calendar has remained the same: bringing joy to people. The Advent calendar is an expression of the uniqueness of the Christmas season and the excitement leading up to Christmas.

Sources

Tina Peschel, Adventskalender – Geschichte und Geschichten aus 100 Jahren (Advent calendars – History and anecdotes), Verlag der Kunst, 2009

Esther Gajek, Adventskalender – von den Anfängen bis zur Gegenwart (Advent calendars – From the beginnings to the present), Süddeutscher Verlag

Esther Gajek, Türchen Auf! Zur Geschichte des Adventskalenders (Doors open! On the history of the Advent calendar) in:

Alois Döring, Dem Licht entgegen (Towards the light), Greven Verlag Köln 2010

Markus Mergenthaler, Adventskalender im Wandel der Zeit (Advent calendars in changing times), Knauf Museum Iphofen, 2007

Thomas Mann, Buddenbrooks – Verfall einer Familie, Fischer, 1901

Dominik Wunderlin, Seit wann gibt es Adventskalender (Since when has the Advent calendar existed), Schweizer Volkskunde, 1980